OVERALL AWARD WINNER 2019

Dinu Li is an interdisciplinary artist working in film, photography, installation and performance. Li examines the manifestation of culture in the everyday, finding new meaning in the familiar, making visible the seemingly invisible. Archives are often used as points of departure for his research based projects that have an emphasis on appropriation and reconfiguration.

Nation Family was made in collaboration with his cousin over a seven-year period. Together, they revisited a former labour camp where his cousin was sent as a nineteen-year-old to work in a rubber plantation. Now one of the most popular holiday destinations for China’s booming domestic tourist industry, his cousin’s past life is recounted by a former comrade and a female peasant. Shifting through fragmented time zones, woodlands and vacant hotel rooms, the film builds to an illogical grand disco dancing finale.

ADDITIONAL AWARD WINNER 2019

Mahali O’Hare’s recent series of paintings have their roots in Classical still life and grow from its traditional language of decadence, impermanence and mortality. Her solitary vases, set against a dark, void-like background, are over painted with landscapes that draw on myths of the forest, the English pastoral, childhood hideaways, Persian gardens and the canon of landscape painting.

The figurative nature of her vases, engulfed by the natural world, embody presence and absence and oscillate between still life, portrait, landscape and figure. They embrace dualities such as contained and overgrown, inside and outside, object and perception. The vase acts as an inverted amphitheatre for these narratives and a shape that works in contrast to the rectangle, directing the viewer into a landscape with multiple perspectives.

AUDIENCE CHOICE AWARD WINNER 2019

Layered fragments, muted tones and lost histories are interwoven into Alia Hamaoui¹s multidisciplinary practice. A combination of print, painting and construction; Hamaoui’s work embodies a shift from physical remnants of the past to the digitising of memories. She is deeply interested in exploring our relationship to memory and how objects and images shape both our collective and personal memories.

Her work is Influenced by craft based techniques such as tiling, textiles and moulding soap, which she combines with digital print and new age media, often alluding to symbols of cultural history, such a relics, souvenirs, statues, insignias and archival imagery. Recent work has taken influence from furniture shapes and how objects with diverse cultural narratives sit together in a functional and decorative manner.

Iain Andrews paintings begin as a dialogue, between a particular Folk Tale and an image from art history that may be used as a starting point from which to playfully but reverently deviate. He is interested in how stories are retold and re-imagined, and how the retelling can alter and embellish the original even as it seeks to render it vital and alive once again for a new audience.

Thick and crusted Areas of poured paint are finely adjusted to create shadow and recession, to a point where a form may, only just, begin to emerge. In this way, Andrews aims to frustrate the process of recognition by treading a path that plays between the borders of figuration and abstraction.

Utilising everyday materials, such as wire, straws, fabric and plaster and intentionally ‘hand-made’ processes, Amanda Benson’s sculptural works employ a sense of impermanence and provisionality. She explores and develops ideas on form, physicality and colour that evolve from sketches or are simply led by the qualities of the materials themselves.

In Pissenlit 4, for example, black annealed wire, straws, fabric and plaster have been used to create a geometric, repetitive form almost on the verge of collapse and yet maintaining a playful cohesive whole. Periodically her works are titled with French words that, whilst not being literally descriptive (in this instance Dandelion), are a play on their sound, meaning and interpretation.

Sara Berman’s practice is bound by a deep interest in materiality and the exploration of the body. She is interested in the space a body may occupy and inhabit: our homes, our clothes, our skin. She also looks to areas such as design, manufacturing, globalisation and commerce, and to shifts in the value systems and institutions that result from this movement in both goods and people.

Her canvases fuse perspectives, patterns and figures, compressing space in such a way that furniture, ornament and body seem to exist on top of one another, sometimes becoming indistinguishable. They regularly incorporate vintage textiles (her series of Dress paintings being applied directly on to antique French smocks) and a recurring ‘Harlequin’ motif applies to the female form, making reference to art historical tropes of the clown, entertainer or whore.

Jack Bodimeade’s work is typically grounded in the process of collecting variations of visual phenomenon, either through online research or by drawing from life on field trips. Recent works are based on his trips to zoos, aquariums and reptile houses as well as frequent visits to draw Victorian concrete dinosaur sculptures in Crystal Palace Park. These drawn images have been combined with video and digital technology, by physically inserting them into holes cut into LCD monitors to create alternative fictional narratives for a range of animals.

Bodimeade’s works, inspired by images of tigers swimming, are used as a proxy for imagining how they might exist living in space, or else for how his static concrete dinosaurs might be released into a more fluid, blurred understanding of time and space.

Harriet Bowman uses an ongoing fictional narrative as a tool, akin to the use of preliminary sketches, to develop ideas and produce new work. This narrative and its fictional, non-human protagonist provide her with space to explore her interest in cars, horses, parenthood and the language of advertising, as well as dealing with notions of grief and loss.

From this text she generates symbolic objects that act as physical footnotes, working in materials such as ceramic, leather, aluminium, hand cream and even crushed children’s snacks. These objects draw out visceral characteristics through material, colour, position and texture and form the individual sculptural elements for her exhibitions and installations.

Patrick Brandon uses an intuitive system of referencing from experience and from the narratives and images of others. Moving between fluency and error, cliché and profundity, hunting down images and stories, he gives consideration to status convention, and differences in subject-object relationships as they appear in art, language, and philosophy. He aims to make things strange and surprising, to play with questions of value, and awkwardly embrace tradition by way of appropriation, care, and subversion.

Text sometimes appears in his paintings, taking the form of semi-erased titular or advertorial expression, more irritant or symptom than signifier. His exhibited works are selected from a wider series of paintings in which historical reference (in this instance Goya and Bruegel) converges with narrative (hunting, finding).

Michael Calver often starts a painting by thinking of something he has noticed on the way to his studio: a tree, the sky or a passing expression on someone’s face. He works at a sustained pace and concentration similar to the experience of drawing from life, except with nothing but a slight sensation or mood to guide him. As a more intuitive working pattern emerges he maintains capacity for some last minute switchbacks when elements demand further consideration, sometimes making alterations months or years later.

Although his paintings On the Beach and Visitors have elements of joy - flowers, white clouds in blue skies and suggestions of rural landscape – in essence, they convey and comment on aspects of human nature that are revealed through aggression, addiction and madness –memory laden paintings, which evoke contingent dramas of despair.

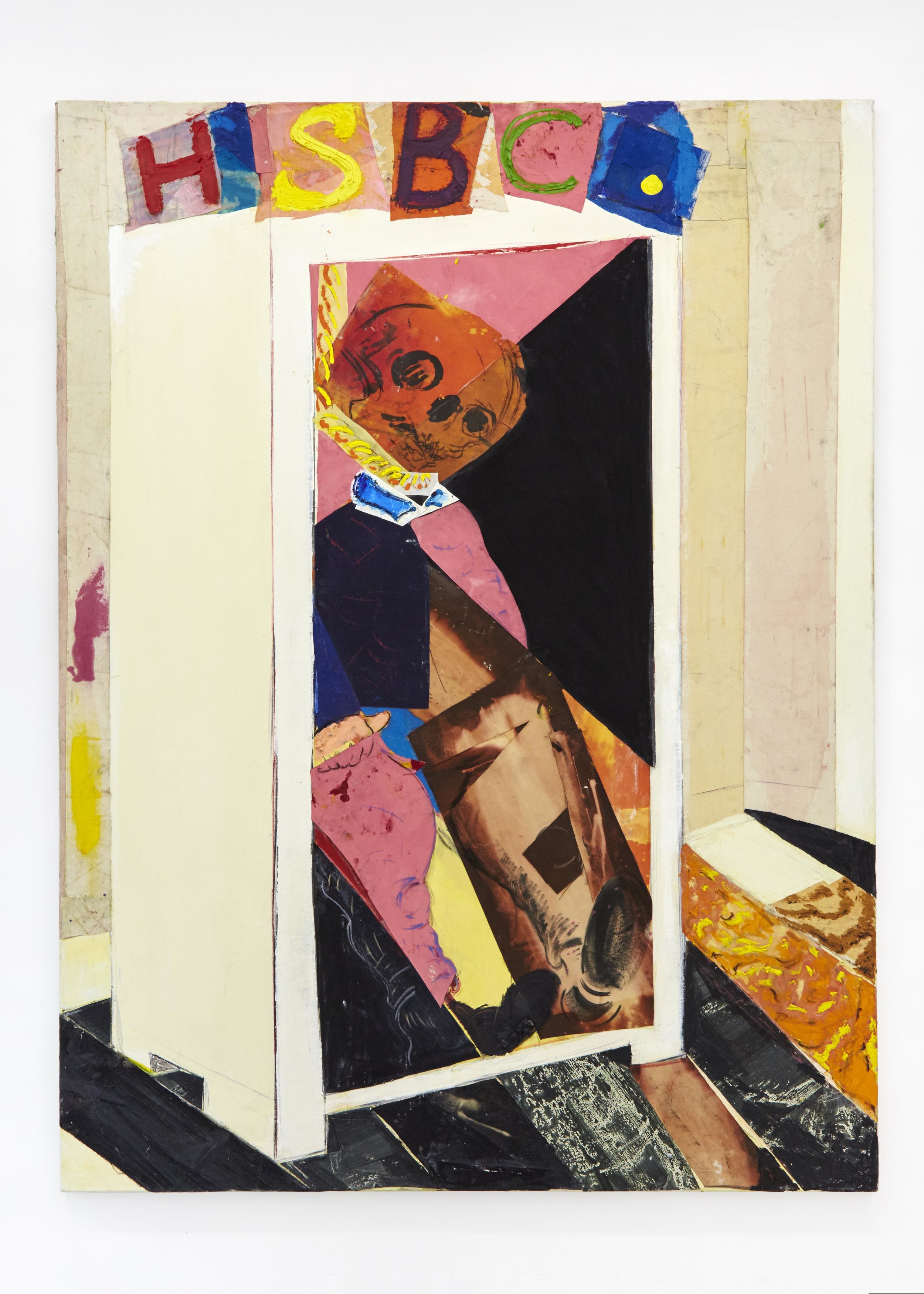

Working across painting, sculpture, collage and text, Grant Foster uses irreverence as a tool to readdress the dogmatic traditions of the past and the present infallibility of reason. Concerned by tabloid culture’s ability to stoke hysteria, he employs an almost cartoonish folk-like aesthetic as a way to challenge the ascendency of classical European figuration. Attempting to re-arrange our common assumptions regarding beauty and the grotesque, Foster’s voice is both tender and hysterical, sardonic and earnest, with black humour running throughout.

He regularly employs a centralised emblematic motif, where a lone figure is engaged in an act of quiet solitude or lurking malevolence and moral ambivalence is a central motivation across his work. High-keyed colour suggests an acidic immediacy that can be both visceral and humorous, where laughter and pathos are keenly entwined.

Jeb Haward’s abstract works are formed through a process of speculation, uncertainty and a willingness to improvise in the moment that contrasts with his innate desire for a preconceived outcome. They bring together a huge variety of components such as recycled parts cut from previous paintings, dirt from the studio floor, glue, pencil, fragments of drawings, paper, pens…whatever comes to hand - the more unlikely the combination, the better.

For Haward, the process of making has become the subject and whatever transpires in the making has to find a reason for existing in relation to the other occupants of the space. Any nagging doubts over the purpose of making images are always overcome by the promise of something new that will emerge that has never existed.

Harley Kuyck-Cohen’s practice explores our domestic lives and the ever-changing boundaries between public and private space. These politics of dwelling are manifested in various media including sculpture, architecture and installation, often incorporating time based assemblages that imply waste and renewal. His work venerates the ways in which we use built space and the idiosyncratic touches and sentiments of dwelling, particularly the vernacular practices of the home, are fictionalised in sculptural form.

By asking what we decide to bring into the future, alternate histories are collated together like a chaotic assemblage exploring the relationship between the old and the new and the corrosion that happens in built structures and textures over time.

John Lawrence works in a variety of media to explore how the dissemination of ideas and ideologies operates through cultural networks. He uses processes of stripping back, editing down and repositioning contrasting source materials to investigate, expose and better understand their elements.

His video work Financial Weather Report IV (Imagine That) combines 1978 footage of the jazz funk band Weather Report overlaid with the subtitles of the 2009 family comedy movie Imagine That. In the film Eddie Murphy's character, a workaholic father, discovers that his daughter's imagination holds the key to his stock market success and, throughout, the financial market is presented as a pseudo-mystical force, outside of our capacity to truly understand or control.

It represents a recurring trend in Hollywood for films aimed at young audiences to foreground aspects of work and capitalist business models within central themes and plot devices. By contrasting the subtitles of such a film against a more collaborative, improvisational and 'free' approach to working with others that Weather Report represents, Lawrence’s aim is to highlight the presence of these thematic frameworks as well as to question the intentions and wider implications of them on developing audiences.

Molly Thomson’s work concerns the performance of the painting as an object, using the conventional painting panel as a springboard for action and a vehicle for thought. She is interested in its resistance and limitations - in what happens when given conditions are subject to question and the boundaries are breached. Her process begins by de-stabilising the traditional rectangular format through acts of cutting that destroy the panel’s symmetry and begin to animate the object; this breaks any illusion of a spatial ‘window’ and can bring the normally invisible sub-structure into play.

Conventionally, paintings present only their facades but these paintings may own up to their internal spaces. Like attitudes or desires, the re-shapings have consequences. Mistakes must be accommodated, new relationships established. Operating between such acts of damage and reparation, she looks for a kind of concentration that can be reached through the excisions, shifts and accumulations.